On Gold Mountain Read online

Page 20

Ray abandoned his resolution to “get the hell out of Chinatown.” In the first place, neither Ray nor Ming had occasion to socialize with what they perceived to be their backward Chinese neighbors. More important, Fong See was still in China. As a result, the entire family was freed from his tyrannical presence. The boys now had the luxury to spend their father’s money—drive fancy cars, buy expensive clothes and gifts, treat their new-found friends to evenings out—without having to justify a penny, listen to lectures, or obey any commands. They could, quite simply, do as they pleased.

Still, shouldn’t Ray, with his dislike for his father, have broken away from Chinatown completely? He certainly could have looked for a job, and perhaps he may have, in a halfhearted fashion. But neither of the older boys had to work; all of their needs were provided for, all of their bills were paid. Why should Ray worry about “living in Chinatown” when he spent most nights sleeping between cream-colored satin sheets in the arms of some lovely woman who willingly accepted him into her bed?

It was the twenties. Ray and Ming didn’t worry about a thing. What little work they did do became just another way to play and have fun. While their mother managed the downtown store, Ming and Ray spent most of their days out in Ocean Park, where they auctioned goods on the boardwalk. In this carnival atmosphere, the elder scions of the F. Suie One Company competed for attention with the roller coaster, dance halls, bath houses, and the splendor of Abbot Kinney’s Venice, just a few blocks away, where crowds clustered to view the curiosities: the charms of Madame Fatima, the snake charmer, and the man who “eats ’em alive!” Along the boardwalk, with its Italian deco buildings, Fong See’s sons set up a tent. To attract passersby, they kicked things off with a vaudeville show, or sold tickets to see the stuffed mermaid. Then they took turns standing on a platform and auctioning off antiques and curios. Customers paid with hundred-dollar bills. Money was coming in so fast the boys could hardly count it.

Their take, considerable in the early years of this cash-crazy decade, was collected in a glass jar during the day, and spent in speakeasies, roadhouses, country clubs, and honkytonks at night. Since Prohibition was in effect, the boys hung out in Venice to the west and Vernon to the east, where “dry” laws were relatively relaxed. Sometimes they’d drive out to the Cotton Club, on West Washington in Culver City, and take over the whole place for a private party. But nowhere were Milton and Ray better known than at the Vernon Country Club, where the swankiest of the swank went to socialize and imbibe the best hooch. They liked to host big parties, hire Gus Arnheim’s band, and generally have a wild old time. Unlike the poor Chinese, who eked out their livings in Chinatown under constant fear from unfair laws and harassment, Ming and Ray encountered no racism. Instead they were accepted for their looks, their money, and their never-ending desire to have a good time.

Ming and Ray cut a wide swath. They looked resplendent in their tuxedoes of exquisite cut. They wore their hair slicked back with bandoline. They could shimmy and tango from one end of the dance floor to the other with every girl in the place and have enough energy (and gall) to start again before the evening’s end. Unlike some of the other young men about town, who babbled silly nothings like “bee’s knees,” “suffering cats,” and “flea’s whiskers”—Ming and Ray could regale ruby-lipped maidens with tales of Peking and Shanghai, of opium dens and Russian princesses.

Young women—their shoulders powdered, their rolled garters showing just above their knees—could tell that these men were rolling in big bucks. They drove the fastest, most beautiful, most expensive cars. They knew the best bootleggers in and out of town. They talked constantly of their plans for making their millions. They had dreams of becoming big land developers, owning penthouses, buying buildings, opening their own nightclub. As most of the young ladies must have noted, to dream such dreams didn’t require any real work. These boys had a rich daddy who, it seemed, would buy them anything. Besides, what girl didn’t like it when a man talked oil? When Milton and Ray mentioned the family property on Signal Hill, there wasn’t a young woman in the county who didn’t know that gushers were blowing in out there almost every day.

Milton’s days as a playboy were destined to be short. On June 11, 1921, in a civil ceremony in Tijuana, he married Dorothy Hayes, a contract player at Paramount. Dorothy, like many who interpreted the federal law against alcohol as all the more reason to drink as much as possible, drank far too much. Ming didn’t hold back either. Their early married years were one long, glorious party.

Still in China and secure in the knowledge that Ticie was taking care of business in Los Angeles, Fong See settled into the routine of a landed Chinese gentleman. After years of curbing his impulse to buy land, he embarked on this enterprise with a vengeance. In the village, people happily traded their mud or brick shacks for American dollars that they could exchange for huge amounts of Chinese money. Buying property in Fatsan for his hotel proved to be more difficult, for on the site that Fong See had chosen stood Bu Sing Huei Kwan, a family association temple that housed records for the Bu Sing clan dating back hundreds of years. Eventually the patriarchs of the Bu Sing fell victim to their own avarice, agreeing not only to sell the property but also the thousand clay statues that had been part of the temple’s religious decoration for as long as anyone could remember. Once the patriarchs had parted with these, Fong See encouraged them to sell the rest: a large, multi-armed Shiva with the sun and moon in each hand, and a set of carved, gessoed, gold-leafed, and painted male and female Ming Dynasty tribute figures.

He purchased all of the temple’s carvings, including an arch that stood twenty feet high behind the main altar. The arch, of carved, gilded wood, portrayed the Eight Treasures: the pearl, the lozenge, the pair of sacred scrolls, the cups made from rhino horn, the coins, the stone chime, the mirror, and the artemisia leaf. Also carved on it were bats, the symbol of long life (Fong See recalled how his father had used dried bat to ensure longevity, good sight, and a general feeling of well-being and happiness); a rendering of a gourd, to remind pilgrims of Li T’ieh-kuai, one of the Eight Immortals, as well as necromancy and mystery. There were phoenixes, deer, doves, two-faced dragon bats—all symbols of good luck, longevity, and immortality. All of these purchases were packed and shipped to Los Angeles.

In early 1921 the construction of the Fatsan Grand Hotel—a modern, four-story structure in a city that had never before had a hotel, let alone one with western-style toilets and bathtubs—neared completion. Fong See conducted daily inspections of the property. As he walked through the main courtyard to the wooden steps that led upstairs to the main entry for the hotel, he could see that work still needed to be done, but it was already evident that the lobby would be very grand. A large front desk of carved mahogany had been installed, which curved from the top of the stairs across the length of the room. At each end of the lobby, floor-to-ceiling stained-glass windows cast a glow of Peking rose, celadon green, and imperial yellow. The window at the front of the hotel looked down to the bustling street below. The rear window opened onto a courtyard that would one day be cooled by the shade of large plants and dotted with tables and chairs for the weary traveler. Across the courtyard he observed workmen painting the building that would serve as his town house.

Wandering through the first three floors of the hotel, examining the heavy wooden guest-room doors with their frosted-glass windows, he conjured up in his mind’s eye the Bradbury Building in Los Angeles, and instructed the architect to have numbers stenciled on each transom. On the fourth floor, Fong See saw, though he didn’t fully understand, how modern the kitchen would be when completed.

A small army of laborers was on their hands and knees, laying tile. He had found a ceramics factory in nearby Shiwan to re-create the intricate designs he had grown to admire in the mansions and great public buildings of Los Angeles. Now, on each floor of the hotel, he found tilework in geometric patterns—some in a star of red, black, and white, others in ribbonlike designs that unraveled

down the long hallways in magenta, puce, and aquamarine.

One sunny morning late in January, sedan-chair bearers, trotting along the raised walkways between the rice paddies, carried Fong See from Fatsan to Dimtao. As he neared the village, he saw the high roof of his nearly completed villa towering over Dimtao’s protective wall. When he reached the gatehouse at the main entrance of his new compound, he was met by his architect, who guided him into a spacious courtyard. Now the courtyard was just rough dirt strewn with the detritus of construction, but in time it would become an arboretum of exotic plants and trees.

Fong See was nothing if not a man with an opulent imagination. Just as the Fatsan Grand Hotel paid equal homage to the art deco sensibilities of Southern California and the famed ceramic works of Kwangtung Province, so too did the mansion in the village. Craftsmen from across the country had been hired and brought to this small village to make stained glass, to chisel teak room dividers inset with glass etched in cloud and dragon motifs, and to draw up exquisite ceramic designs that would then be manufactured in Shiwan, as they had been for the hotel.

He paid attention to every detail. Sewer pipes—a mystery to both the architect and the laborers, and therefore exposed throughout the house—were embellished with glazed ceramic floral garlands in yellow, green, white, and pink. Above each of the windows were delicately rendered three-dimensional glazed birds reminiscent of those found in the thousand-year-old Temple of Ancestors in Fatsan. Decorative carved and enameled landscapes graced the second-story veranda. On the more practical side, this would be the first house in the history of the village to have glass windows and western-style toilets.

Fong See climbed to the spacious sheltered pavilion on the roof to survey his domain—the fields afar, the brick and mud huts of his cousins and the peasants who worked in his fields below. It only pained him that his mother would not live to see the completion of these efforts—the culmination of her own hard work and sacrifice. In recent days, Fong See had hired four men to lift her onto a long rattan chair and carry her through the village to view the house. He promised himself that he would stay in China until Shueying died. When she joined her ancestors, he would personally see to the professional mourners and the banquet.

For all of these efforts, the villagers praised Fong See. People liked to tell the story of the time the noodle peddler came through Dimtao while Fong See was taking a walk, and Gold Mountain See had bought noodles for each of the villagers who had gathered together to chat under a banyan tree. Because of this and his other charitable deeds, the villagers protected their Gold Mountain See during his time in Dimtao. “He is a very important person from the Nam Hoi District,” they told each other. “Whenever people ask if he is Gold Mountain See, we must deny it.” Every time they denied his identity—and another gang of potential kidnappers was thwarted—Fong See would host another banquet. He relished their approbation, which made him feel strong and powerful.

Today, before leaving the village, he ordered a stone carver to inscribe a piece of marble with the blessing “Happiness Is Coming Through the Gate,” to be inset above the porticoed entrance to the house. Fong See also instructed an artist to paint the characters of two Confucian couplets—one stressing family harmony, the other divining family prosperity—to hang on either side of the front door. Of course, there was just one problem. Whom could he trust to take care of it all when he went home?

Fong See had the mansion, the Fatsan Grand Hotel, and the ongoing export business for the F. Suie One Company. He also owned factories that made paper goods, firecrackers, baskets, and kites. He had built his empire on the sweat, blood, and trust of his family members. It would have been inconceivable for Fong See to bring in an outside person to manage things. Uncle was a logical choice, but recently he’d shown signs of dissatisfaction with his position within the F. Suie One Company. Fong See had then settled on Eddy, but Ticie wouldn’t hear of it.

A year had passed since Ticie had returned to Los Angeles, and Fong See still hadn’t completely forgiven her. He still didn’t understand why Eddy couldn’t have stayed in China, when Fong See himself had been on his own, selling matches in Canton when he was only seven, and had married and gone to the Gold Mountain when he was Eddy’s age. But Fong See also knew that his disagreement with his wife went far beyond whether or not Eddy should take care of business in China.

The way Fong See saw it, Ticie wouldn’t obey him, didn’t respect him, and refused to see him as the person he had become. He was no longer a young Chinese man striving to get ahead in a foreign land; after years of struggle in Los Angeles, he realized that he could only achieve limited success. In China he could reach as high as he wished; he could use his money and influence in any way he chose. All of the things he had dreamed about in Los Angeles were actually possible for him in China. Here he was Gold Mountain See—landowner, exporter, headman of the village. But he couldn’t maintain this position without help.

Without a blood relative in China on whom he could rely, Fong See decided that Ming should marry a local Chinese girl with a competent family. Through a go-between, Fong See found sixteen-year-old Ngon Hung, whose name meant “Red Face,” from Nam Bin village in Fong See’s own Nam Hoi District. Ngon Hung supported herself by making firecrackers. Each week she went to a factory where she picked up thick red paper, took it home, and, with the grace that came from countless repetitions, rolled the paper into red casings. Next she hammered the bottom to close each firecracker, leaving the top open, and finally she packed them upright into huge rounds to be returned to the factory where other workers would insert wicks and powder.

Ngon Hung was the only child of a widow, Fong Guai King, who was rumored to be business-minded, level-headed, and organized. Indeed she must have been, for when Fong See met Guai King, even though she was a foot-bound woman, he decided to entrust his many interests to her. They negotiated a bride-price for Ngon Hung. All that was needed was a groom.

No one living today remembers exactly what transpired, and, as is often the case with deceptions, the record is shadowy. One story is that Milton was sent for, and when he arrived in China, his father reminded him of the plight of Chinese bachelors in Los Angeles and what they wouldn’t do for a wife. But Milton balked at marrying the peasant girl. He was a playboy, after all, used to fast women and fast cars. Unwilling to lose face, Fong See married the girl himself and, in traditional fashion, the bride didn’t see her husband-to-be until the wedding night. Instead of a young and handsome groom, she discovered a man with graying hair who was already shrinking with age and complained constantly of scratchy skin.

In this scenario, the fact that no one mentions that Milton had already married Dorothy Hayes presumably shows that the city-wife/village-wife tradition was an accepted pattern in the family. Nevertheless, immigration records show that Milton didn’t go back to China in 1921 or 1922. However, he did return in 1925, and it’s possible, though highly unlikely, that even at this late date (after Ngon Hung had already given birth to a daughter), Fong See still wanted him to marry the girl. In fact, there is another story that Milton wanted to take a second wife during his 1925 trip to China, but that the bride-price couldn’t be resolved.

The most reliable version is that Ticie was in the store and noticed Uncle acting strangely after receiving one of her husband’s letters. She asked Uncle to translate the whole letter, but he refused. For years they had worked side by side, Ticie doing the books in English while Uncle did them in Chinese. “You’re a good woman,” Uncle is reputed to have said. “You’ve slaved alongside him and helped him make money.” Then he wrote his brother to suggest that he renounce this new marriage: “Ticie has been a good wife to you. You promised our mother that Ticie would be your Number One wife. You can’t have a better person than Ticie.” All this may be true, but Uncle still couldn’t bring himself to tell Ticie what his brother had done.

And yet somehow word got out in Chinatown about what Fong See was up to. Rumors passed from mouth to m

outh, from store to store, with the fury and speed of those who wish harm on the mighty. Jennie Chan, Sissee’s old friend, must have experienced a certain malicious glee in confronting the girl who had shown off her wealth with movie tickets and boxes of candy. “I hear your father has another wife,” Jennie said. “Everyone in Chinatown knows about it.” It was news to Sissee, just as it was news to the rest of the family. Finally, Ticie stole the letter Fong See had written Uncle, took it to a professional letter reader, and discovered positive proof that her husband had married again. As Ticie railed against Suie, Uncle tried to intervene. “Don’t be so hardheaded,” he told her. “Don’t close your heart. Don’t be stubborn.” Like her husband, Ticie didn’t listen to Fong Yun’s advice.

For years the family maintained that this third marriage was simply a business arrangement. But as relatives have died and morals have changed, the family has loosened its view. “My grandfather had no reason other than his own whim,” says Richard, my father. “He was just a horny old man.” Sumoy, the youngest daughter of Fong See and Ngon Hung, believes that her mother was brought to the United States as a young “cousin” or “niece,” and not as a wife at all. “My mother was beautiful, and this was a chance for her to come to America,” Sumoy says. “She was surprised to be marrying my father, but she wasn’t shocked. She had been told that this person would take care of her. She wouldn’t starve, and her mother would be taken care of, too.”

Sumoy believes her father regarded the marriage as a way of showing his status. “My father was successful, and he was telling the world he could have a teeny-bopper. He could say that he was still able to produce children and could provide for them. To have a wife from China and to keep her in the Chinese tradition made him feel stronger.” Of the marriage between Fong See and Letticie Pruett, Sumoy adds, “She had four boys, and for a Chinese family to have that many sons is a feat in itself. But to surmount the odds”—the miscegenation laws and the racist attitudes of Chinese and Caucasians—“they must have had a great love.”

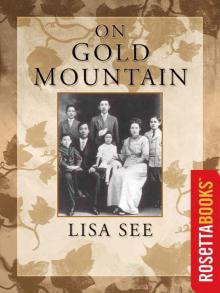

On Gold Mountain: The One-Hundred-Year Odyssey of My Chinese-American Family

On Gold Mountain: The One-Hundred-Year Odyssey of My Chinese-American Family Snow Flower and the Secret Fan

Snow Flower and the Secret Fan Peony in Love

Peony in Love Flower Net

Flower Net Dragon Bones

Dragon Bones Shanghai Girls

Shanghai Girls Dreams of Joy

Dreams of Joy The Island of Sea Women

The Island of Sea Women The Tea Girl of Hummingbird Lane

The Tea Girl of Hummingbird Lane China Dolls

China Dolls The Interior

The Interior On Gold Mountain

On Gold Mountain