Dreams of Joy Read online

Page 36

“Be careful,” Dun says. “Come back to me.”

“I will,” I tell him. As we embrace, I whisper in his ear, “I love you.”

Then Z.G.’s chauffeur hands me the car keys. I open the backseat door for Z.G. Once he’s inside with the blue curtains drawn, I walk around to the driver’s side, get in, start the ignition, and put my foot on the gas pedal. At the corner, I look in the rearview mirror for one last glimpse of Dun.

On the outskirts of Shanghai, we pass a camp that’s been set up to hold peasants who’ve been captured trying to enter the city illegally. From here, the drive is extremely slow. The roads are terrible—at times almost impassable with mud and ruts—but roadblocks are our biggest problem. We’re stopped every few miles to have our papers checked. We’re going against the tide. The roadblocks are to prevent even more peasants from leaving their villages to come to cities—and how many people we see being turned away and sent home. Even though we’re going in the opposite direction, my hands sweat and my heart races at every checkpoint.

We reach Tun-hsi around midnight. We check into a guesthouse, but how can we sleep? The next morning, we go downstairs for a meal. It’s a crisp spring morning and we sit outside at a table under a tree. The innkeeper won’t accept our city rice coupons, so we can’t have porridge. Instead, we’re served a soup made with water greens and water. Then it’s like one of those scary movies Joy liked to watch on television. People—walking skeletons, zombies—begin to emerge from corners, alleys, and homes. They stare at us as we eat. The minute we stand, a couple of them bolt from the crowd, grab our bowls, and lick them clean.

A FEW MILES out of Tun-hsi, a nightmare landscape appears before us. People dressed in rags crawl by the side of the road. Dead bodies lie splayed in the fields and dot the road. The smell should be atrocious, but the corpses have no blood or meat left to decay. They’re like mummies—gray and emaciated. Wild dogs are plentiful, and they feast on the dead. I drive slowly, swerving from one side of the road to the other in an effort to miss the gruesome obstacles. Z.G. sits behind me. We could still be pulled over, and the master would never ride next to the driver. I keep glancing in the rearview mirror. Z.G.’s eyes are wide with shock. We’re both terrified for Joy.

I come around a corner and brake as hard as I can. A couple lie in the center of the road. I can’t drive around them. We sit in the car, the engine idling.

“What should we do?” I ask, my hands gripping the steering wheel.

“Let’s give them something to eat. Maybe we can move them that way.”

I don’t want to get out of the car, but I do. Z.G. and I look in the trunk and pull out some crackers. We walk tentatively toward the couple, both of us holding our crackers at arm’s length. The man reaches forward to grab Z.G.’s cracker and then collapses, dead. The woman takes the cracker from my hand, clutches it to her chest, and curls into a little ball to protect it.

“You should try to eat it,” I say softly. The woman stares at her dead companion, her eyes unseeing, her treasure protected. It’s as though I’ve given her the most precious Christmas gift possible, something that should be saved and cherished—never broken, let alone eaten.

Z.G., showing nerve I didn’t know he had, grabs the dead man’s heels and pulls him to the side of the road. Then I help him move the woman. As soon as we’re done, he gruffly says, “Come on. We need to keep moving.”

Several more times, we have to stop to move the dead or dying from the road. The sun shines resplendently overhead. Always I expect silence when I get out of the car—no singing, no sounds of working in the fields, no braying of animals, no birds trilling—but cicadas, immune to the concerns of humanity, drone steadily. Then, at one of our stops, cutting right through the cicadas—and piercing into my soul—children and babies yelp, sob, and whimper. Z.G. and I scan the fields, searching for the source of these sounds that seem to come at us from every direction.

Ahead of us something moves—bouncing angrily—not far from the side of the road. It’s a small girl’s head and shoulders. The parents have dug a hole deep enough to prevent escape and abandoned their daughter in it. They must have hoped someone would stop and take her home. I take a few steps forward so I can see down into the hole. The girl’s naked. Her skin hangs like wrinkled tofu skin, and her belly is swollen and purple. Then Z.G. grabs my shoulders.

“Look.” He points to different spots in the field.

Other children and babies have been abandoned in these pits too. They’re everywhere. I think I’m going to be sick.

“This is horrible, but we have to go,” Z.G. says.

“But—” I gesture to the field.

“We can’t help them. We have to get Joy and her baby.”

I’m overcome with despair. If I save even one of these children, then I might be too late for my own flesh and blood. I close my ears and my heart, get back in the car, and continue driving.

Finally, we reach the old drop-off point for Green Dragon Village. Since the director of the Artists’ Association called ahead, I expect to see a welcome party, as we had the last time we came. Instead, the road is ominously empty and quiet, while the footpath we used to take to Green Dragon has been blocked with sawhorses and other junk. A sign with an arrow to the Dandelion Number Eight People’s Commune points to a new road that cuts through the fields and veers around Green Dragon’s enveloping hills. The commune’s cadres wouldn’t have done this unless they wanted us to see Joy and the baby there—at the site of the mural.

I take the road to the center of the commune. Here’s the Happiness Garden for the aged, the nursery, and the clinic. The canteen’s cornstalk walls, however, have broken apart and the roof has collapsed. And there, just as in the photographs Joy sent, is the leadership hall with its critical but stunningly colorful mural. Next to the hall, small children jump and play on piles of what looks to be freshly cut hay. They clap their hands and cry out, “Welcome! Welcome!” They perform as though their lives depend on it, and maybe they do, because their stomachs are distended from hunger and the look in their eyes is not something anyone should see. A group of adults, clean but grotesquely thin, hold signs with words of gracious salutation and sing the usual Great Leap Forward songs, but there’s no honest enthusiasm—or energy—from them either.

Brigade Leader Lai steps forward. He looks the same as when I last saw him. He greets us and gestures for us to enter the building. I hurry inside, expecting to see Joy. After all, she wrote the letter. It could only have come with the brigade leader’s knowledge. In fact, now that I think about it, he probably took the photographs of her and the baby. A round table is set for a banquet.

“We have prepared a twenty-course banquet for our honorable guests,” Brigade Leader Lai announces.

The table is set for three.

“Where is my daughter?” I ask.

“She and the artist are at home. There is no need to see them. Enjoy! Enjoy!” He clasps his hands expectantly. “After dinner, Li Zhi-ge can present his award.” He bows his head deferentially. “I hope I’m not presuming too much—”

I run back outside. The men, women, and children, who moments before were jumping, waving, and singing, sit on their haunches, shoving small balls of rice—presumably a reward for their performance—into their mouths, while a guard keeps watch. I can reach Green Dragon on foot in about ten minutes. If I drive back to the original crossroads and then walk, it’s a few miles.

Z.G. takes my arm. “Let’s go.”

We hurry along the path that runs next to the stream. In minutes, we cross the little stone bridge and enter Green Dragon. Bodies lie everywhere. The smell wasn’t so bad on the road, but here the odor of death and decay is noxious. I look up the hill to Tao’s family home. I don’t see any signs of life, but then the whole village is deathly quiet.

Z.G. dashes up the hill. I follow close behind. The door to the house stands open. The outdoor kitchen looks like it hasn’t been used in some time. Three rusty whee

lbarrows tilt against the wall. That same broken ladder still lies at a haphazard angle. No one has righted it since the first time I came here.

Z.G. stares at me. His daughter, my daughter—she’s inside. I take a breath to steady my heart and prepare myself for the worst thing a mother can imagine.

We enter the house. The room is dark, cold, and dank. Shredded paper hangs from the windows. Sleeping mats stretch across the floor, but no one is on them. Then, in a corner, I see a slight movement. It’s Tao. He looks bad.

“Where is Joy?” I ask.

I follow the direction of his eyes and see a heap of padded clothes in another corner. I run across the room and kneel next to the pile. I pull gently on it, and it falls forward. It’s Joy. Her skin looks like old parchment. Her cheeks are hollow and her lips have a bluish tint. I suck in air, sure we’re too late, but the sound causes her eyes to open. They burn bright—staring in an unseeing, feverish way. Her mouth moves, but no sound comes out. “Mama.”

I swallow my terror and fear. I can’t be too late.

“Z.G., boil some water. Hurry.”

While he goes back outside, I peel away more of Joy’s clothes, and there tucked against her naked but shriveled breasts is my granddaughter. She too is alive. I open my bag and bring out the packet of brown sugar I brought with me. I take a few granules and drop them into Joy’s mouth. Then I do the same to the baby.

Z.G. returns with a pot of hot water. I make a weak tea of brown sugar and some slices of fresh ginger. While Z.G. stirs the concoction, I look for a knife. I slice open my arm and let the blood drip into a cup. For millennia, daughters-in-law have done this for their mothers-in-law out of respect and reverence during times of famine. I do it because I love my daughter. Z.G. wordlessly pours the tea over the blood. I spoon a bit into Joy’s mouth while Z.G. blows on another spoonful to give to the baby. Our eyes meet. What now?

I’m torn. Should we stay here and build their strength or try to get them back to Shanghai as quickly as possible? What will happen when the brigade leader realizes we want to go back to Shanghai? It’s clear he’s been hoarding food while the people in the commune have been dying. What would the punishment be for that, and what would the brigade leader be willing to do to keep his activities a secret? We have to get out of here and we have to hurry.

I feel hopeless. Z.G. is just an artist, a Rabbit artist at that. He’s not good in an emergency, but then I realize with sudden clarity that I’m not either. My sister always got us out of trouble. What would May do? After I was raped and my mother died, May put me in a wheelbarrow and pushed me to safety.

“Can you push a wheelbarrow?” I ask Z.G.

We grab some quilts and tuck them into two of the wheelbarrows to provide cushioning. Then Z.G. carries Joy and the baby outside and lays them on the quilts. While he goes back to get Tao, I give Joy more of the blood tea and half a cracker that I’ve pre-chewed. Z.G. reemerges from the house, supporting Tao, who has just enough strength to walk. Joy sees him and begins to mutter and shake her head. “No, no, no.” She must be delirious.

I smooth hair from her forehead. “Everything’s going to be fine now.”

Joy turns her head and closes her eyes. Z.G. and I heft our wheelbarrows and begin to walk. The first part is easy. Joy barely weighs anything and we’re going downhill. We turn right at the villa. When we reach the front gate, I stop.

“Wait,” I call ahead to Z.G. I run inside the villa. Kumei, Yong, and Taming aren’t in the kitchen. I hurry through the courtyards to Kumei’s bedroom. She lies on the bed. Ta-ming sits cross-legged next to her. Flies feast in the corners of his mouth and eyes. He’s a bundle of protruding and crooked bones. His eyes are vacant.

“Ta-ming,” I beckon softly.

He continues to stare at his mother, unable, it seems, to expend the energy to turn his head. I slowly approach so as not to frighten him. The truth is, he may be beyond frightening. I try to rouse Kumei, calling her name and shaking her. She doesn’t open her eyes and her body remains limp. It’s too late to do anything for her, but I can’t leave Ta-ming—not after leaving all those other children and babies in the pits by the side of the road. As for Yong, there’s no way she could still be alive. I take Ta-ming’s hand, and he looks up at me.

“Can you walk?” I ask.

He moves like an ancient—brittle, deliberate, and slow. I go to the chest in the corner, grab some clothes, the boy’s violin—about all that’s left from his inheritance from his father—and some drawings that Kumei did in class with Z.G. Then we walk back through the silence of the villa’s courtyards and corridors. Once he and his worldly goods are stowed in the wheelbarrow next to Joy, I pick up the handles and we begin to walk back to the center of the commune.

I’m terrified about what will happen when we reach the car. Miraculously, the brigade leader and his guards are nowhere in sight. We don’t have time to wonder where they are or what they’re planning. Z.G. and I quickly pile the four nearly lifeless bodies in the backseat. Z.G. joins me in the front seat, I gun the motor, and we begin the long and grisly journey back through the death roads toward Shanghai.

I wish we could drive straight out of the country. Go north to the Soviet Union? That might be worse than where we are now. Go south to Canton and hope we can cross the border? That would be a brutally hard and long journey, taking weeks of travel over dirt roads and through numerous guard posts. Joy and the others wouldn’t make it. We have to go back to Shanghai for them to build strength (if they live), gather money and food (if I can find them), and make an escape plan (if we survive that long).

We stop where we can to buy a bit of food, doling it out to Joy, Tao, and Ta-ming in one or two bites at a time so their stomachs will adapt and accept the sustenance. We give the baby bottles of watered-down soy milk, trying not to overwhelm her weakened system. The boy hasn’t spoken and the baby’s cries are weak. Neither Joy nor Tao has much to say. Talking takes too much effort. At night, I pull the car far from the side of the road. Z.G. helps Joy to the front seat, where she sleeps with her head in my lap. I’m exhausted, but I stay awake, watching my daughter’s chest rise and fall with each breath.

When we near the roadblocks preventing the masses from entering cities like Hangchow and Soochow, Z.G. returns to the backseat and pulls the curtains. Much to my relief, we pass through most of the security posts without difficulty. We were here a couple of days ago, and the young men with their machine guns still remember the limousine with the blue curtains. Additional questions are unnecessary.

It takes us five days to reach the outskirts of Shanghai. A little food, plenty of water, tea, and soy milk have considerably revived our bunch. Looking in the rearview mirror, I see Joy staring out one window while Tao leans on the other side of the seat, staring out the other. Ta-ming sits between them, eyes straight forward, seeing nothing.

Remembering the last big checkpoint with the camp for those who’ve tried to enter the city illegally, I pull off the main road and drive to a secluded area. Z.G. and I do what we can to make Tao and Joy presentable. I brush Joy’s hair and pin it into a bun at the nape of her neck. Z.G. dresses Tao in one of his shirts and buttons it. We have only four travel permits. The sentries outside Shanghai are bound to be more inquisitive than those in the countryside. The baby can easily be hidden under Joy’s blouse, but what can we do about Ta-ming? I take him to the back of the car and open the trunk. He grips my hand tightly.

I kneel down so we’re eye to eye. I hold his shoulders and speak directly to him. “You have to get in here. It’s going to be very dark and very scary. You’ll need to stay silent. But it won’t last long. I promise.”

I tuck him in the trunk, put his violin case in his arms for comfort, close the lid, and drive back to the main road. Coming from this direction, we can see into the camp, where bodies have been dumped in a big pit. I brake at the final roadblock and hand the guard four sets of papers. He leafs through them suspiciously. When he peers over my shoulder to s

ee into the backseat, Z.G. snarls at him. “We’re on important business. Step aside and let us through or I’ll report you!” It sounds tough, and the guard obeys. I’m the only one who hears the fear in Z.G.’s voice. As soon as we pass into the city proper, I drive down an alley and get Ta-ming out of the trunk.

“You’re a good boy. A brave boy.”

He doesn’t acknowledge me. I understand his numbness. I went through it myself twenty-three years ago, when I fled Shanghai.

Two hours later, Z.G. and I sit at his dining room table. Joy and Tao rest on separate couches in the salon, where we can see them. They’re too weak to walk upstairs to the bedrooms. Z.G.’s servants have made a clear soup. I still won’t allow Joy and Tao to feed themselves. Their temptation to gorge would be too great. Fortunately, they don’t have the strength to fight and lie there docilely as two of the servants spoon broth into their mouths. Ta-ming, young yet remarkably resilient, sits at the table with Z.G. and me. The third servant brings a tray with dishes, chopsticks, napkins, a teapot, and teacups. The tray just has room for a small bowl of rice, which fills the room with a homey and safe fragrance. She sets the bowl in front of Ta-ming before returning to the kitchen for the rest of the meal. The boy stares at the rice. Then Z.G. and I watch as he counts out one grain of rice at a time—one to Z.G., one to me, one for himself—setting them on the table in three small piles. This is how hungry they once were. Life and death are separated by a thread or, these days, by a few kernels of rice.

Joy

THIS IS JOY

THE KITE DIPS and whirls. Ta-ming holds the controls, but the pull of the wind against the kite is so strong that Z.G. stands behind the boy, steadying his shoulders. This isn’t just one kite at the end of a string. Z.G. and Ta-ming have put up a whole school of goldfish, each one with unique tails and fins. Next, it might be a flock of butterflies with wings that flutter or maybe a flock of cranes against the brisk fall sky, soaring and diving on the breeze.

On Gold Mountain: The One-Hundred-Year Odyssey of My Chinese-American Family

On Gold Mountain: The One-Hundred-Year Odyssey of My Chinese-American Family Snow Flower and the Secret Fan

Snow Flower and the Secret Fan Peony in Love

Peony in Love Flower Net

Flower Net Dragon Bones

Dragon Bones Shanghai Girls

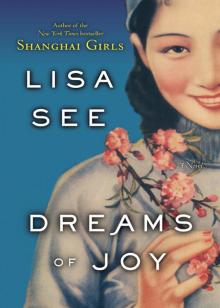

Shanghai Girls Dreams of Joy

Dreams of Joy The Island of Sea Women

The Island of Sea Women The Tea Girl of Hummingbird Lane

The Tea Girl of Hummingbird Lane China Dolls

China Dolls The Interior

The Interior On Gold Mountain

On Gold Mountain