On Gold Mountain Read online

Page 46

Carolyn went downstairs and called her dad, who came straight over. Instead of punching Dick in the nose, as some fathers might have done, George shook his hand and said, “I’m sorry we have to meet like this, pardner.” George helped Carolyn pack. He took her to lunch, told her to “stay out of trouble,” and dropped her off at another rooming house. Noticing that the place was inhabited by hookers, he suggested that she might not want to stay there too long. Then he drove off. Kate was equally unhelpful. Hearing the news that her daughter had been living with someone, Kate didn’t wash her hair for three weeks. “You’re just like your father,” she wailed.

Now batting 0 for 4, Carolyn moved into another furnished apartment, this one just two blocks from City College, which had a fake window with a curtain draped in front of it. From her new place, she began to write Richard, who was stationed in Newfoundland, and he wrote back.

[undated]

Dear Carolyn,

I am now a prisoner of the United States of America, in other words, I am still in the U.S. Army. I am now living on a sort of Arctic Devil’s Island. I’m stationed at McAndrews Air Base, in Newfoundland. The country is rather beautiful around here, but it is extremely difficult to see beauty when you are living under certain conditions. My main diversion has been drinking, with frequent intellectual discussions with numerous eccentric people added to spice up life, and perhaps the occasional pillow fight to get rid of pent-up aggressions. Otherwise life is quite dull….

BY ORDER OF PRIVATE SEE

December 11, 1953

Dear Child,

I must see you on my leave. Among other things I can make indecent proposals to you (or should I say propositions) and also insult you in all kinds of devious and subtle ways….

Sumoy, as an item of oblique interest, intends to get married within the next few weeks or months. This of course makes me extremely happy…. She is not marrying me by the way. Oh well.

December 23, 1953

You asked about Chiang and Mao, I prefer neither. The Chinamen I like are Chuen, Grandpappy, Tyrus Wong, Albert Wong, Sumoy, Buddha (who was an Indian—sorry), and a few others too obscure to mention. Mao and Chiang are just crazy mixed-up old gentlemen that I never met and therefore can form no definite opinion as far as my liking or disliking them.

Dicky Boy

Lover First Class See

January 1, 1954

I don’t know when in the hell I’ll get the goddamn leave now—I don’t know if I’ll get a leave at all…. The leave, it seems to me, wouldn’t accomplish exactly what I had planned—I had thought we might shack-up for approximately two weeks—but apparently I misjudged you—so to hell with it—Yes—you’re a person, a very wonderful fine person, you’re crazy, mixed-up, cool, you go to my head. You’re all kinds of nice-nice and goodie-goodie—but I don’t think I’m in love with you—and I’m pretty sure I’ll never marry you—and even more sure that if we did marry it would be a mess, but I think I’d like to sleep with you—or any other fairly good-looking girl between the ages of 13 and 52 (if well-preserved). By the way, how old is Marlene Dietrich? Did I tell you I was going to marry Pier Angeli, Eartha Kitt & Gigi (Audrey Hepburn), with sex and kisses….

January 25, 1954

I’m so happy to get out of this stinking hole….

P.S. My next play will be entitled, “How Wide Thy Pelvis!” or “How Wide They Pelvis?”

By the time Richard arrived in Los Angeles at the end of January and knocked at the door of Carolyn’s room, it was, as they say, a done deal. A mild feeling of doom surrounded the whole encounter. Richard driving up, climbing the stairs, expecting—what? Carolyn, sitting in her room, waiting, answering the door, and saying, “We have rules here. I can’t close the door if you’re in here. I can’t even have men in my room.” Then climbing in the car, driving desultorily through the city, stopping for dinner at a forgotten restaurant, going back to Richard’s parents’ house on Lantana, walking through the house to the screen porch behind the kitchen, and finally “doing it.” (Of this “it,” so long anticipated and hinted at, Richard has said, “That was the first time I’d ever done that sort of thing. I liked it a lot.”)

Carolyn and Richard spent the rest of the furlough together. They went to the beach. Richard, who had heard Charlie Parker, Les Powell, Lester Young, and Lionel Hampton in New York on his way to Newfoundland, took Carolyn to the Haig, on Wilshire Boulevard, to hear Gerry Mulligan and Chet Baker. Carolyn dressed in black, listened attentively, didn’t move a muscle, and got “very drunk.” They made themselves part of the arty crowd, knowing that if they weren’t, then who was? They went with Chuen and Allen Mock (a neighbor in Chinatown, who was studying to be an architect) to the Beverly Cavern. They went to see One Summer of Happiness, a Swedish film about young love, then spent the rest of the evening discussing adolescent awakenings. They went to see Ninotchka and ate pizza. Almost every other day of the first week, they drove up to the lot on Landa that Stella and Eddy had bought years before, sat on the rim of the ravine, and talked.

“My dad owns this land, and when we get married we’ll have Allen draw up plans,” Richard said.

And Carolyn, who hadn’t lived in a house with more than one bedroom since she was eleven, asked, “How many bedrooms shall we have?”

“We don’t want bedrooms. We’ll just have one great room and live all together in it.”

“What about kids?”

“Eight, at least. Sixteen is better.”

“Isn’t that a lot?”

But Richard’s position was that he was a lonely child, practically an only child.

Carolyn, ever practical, asked, “How will we raise them? What will we do for money?”

“Should I work?” he mused. “I don’t think so. In the Chinese tradition, the son of a wealthy man is expected not to work as a sign that the father is rich.”

“We’re not in China. And your father isn’t rich.”

“All right, then. I’ll be a gardener in a convent.”

“No, you won’t. You need to make a living and support your wife and children.”

“Maybe we shouldn’t get married after all,” he said. “You’re too conventional.”

It was a thirty-day leave, and by the middle of the second week, Carolyn’s period was seven days late. It was ten weeks too early for a rabbit test, which was the only sure way to determine whether she was really pregnant. She was too scared, too poor, and it was too early to go and get an abortion. All Carolyn could do was try various folk remedies; all Richard could do was try to figure out what to do when he had just two weeks left of his leave. Now instead of romantic tête-a-têtes on a ragged hillside, Carolyn—her ears ringing from high doses of quinine and sick to her stomach from taking castor oil—sat in a steaming bath, trying to boil away the theoretical baby, while Richard sat on the edge of the tub, trying to wish it away.

“If you’re pregnant,” he said, “I want you to go ahead and have the baby.”

“If I’m pregnant and you just go back to the army … well, you can just forget that.”

Richard fell back on the same lines he’d used in high school. “Do I really love you? I’m not sure. I’m so sensitive.”

“I’m seeing how sensitive you are.”

“I’m only twenty-four,” he insisted. “And you’re my first girl.”

Carolyn considered, thinking, That’s true, but I don’t exactly see anyone else falling all over themselves to be with you.

He said, “I haven’t seen the wider world. I’m too young to get married.”

“Well, I’m only twenty, and if I’m pregnant …”

“But I didn’t come back with the intention of marrying you.”

“What about your letters? What about all your proposals?”

The only true answer to these questions would have been “Hey, I was only trying to get laid.” Richard was just wise enough not to let those words fall from his lips.

Always the discussion drifted b

ack to the problem at hand. “If you’re really pregnant, I’ll be happy to marry you when I get back. But I don’t want to marry you now.”

“That’s fine,” Carolyn answered stiffly. “If I’m not pregnant, that’s fine. Just fine! But I’m telling you, Richard, if I am, you can just forget it.”

In this atmosphere of mutual trust and love, they decided to get married, because Carolyn’s period was now almost two weeks late, and Richard had to go back to Newfoundland. It was the fifties, and they felt they had no other choice. Yet none of what followed was done in a sad atmosphere. They liked each other a lot. “There was something jaunty about the whole thing,” Carolyn remembered.

On February 18, Carolyn and Richard drove to the store on Ord Street. Richard had told his parents about his engagement the night before, and they were waiting to see this Carolyn Laws. Stella gave Carolyn a hug and said, “So this is the little girl Richard is marrying.” Then they walked back along the main aisle of the store—past the bronze room, the art room, the ceramic room—and into the back office, where Eddy waited for them.

He was beside himself. “This is a terrible idea!” Eddy yelled, whacking his hand through the air like a karate master trying to split a pile of bricks. Half of Carolyn’s mind absorbed what he said; the other half seemed mesmerized by Eddy’s gyrations.

Richard, bound by silence concerning their real reasons, said, “We think it’s a good idea.”

“It’s the worst idea I’ve ever heard! It’s indiscreet!” Eddy shouted.

Carolyn, who’d survived her mother’s fits, stared at him and thought, Oh, have a tantrum. Just go ahead. It won’t change a thing.

But when Eddy went on about how special the family was and asking who she was to be marrying into it, Carolyn began to burn.

“You’re not just marrying Richard,” Eddy said. “You’d be marrying into our whole family …” The way he let that hang, she knew he was saying she wasn’t classy enough or good enough for their son.

Stella sat nearby, wringing her hands and saying, “I don’t get it. I just don’t understand.”

On the face of it, Eddy’s reaction seemed strange. After all, though the particulars were different, Carolyn was as much an “orphan” as Ticie and Stella. But Eddy didn’t see it that way. Perhaps he recognized that Carolyn was—despite her naiveté about birth control, which he didn’t even know about—a modern woman. She had ambition. She wanted a career. Ticie and Stella had worked, but it was always in the family business. Carolyn, on the other hand, looked outward. Perhaps Eddy recognized that she was never going to put the See family first.

“Well, you certainly can’t get married without asking Pa,” Eddy spat out. Carolyn took that to mean that Fong See would say no and the whole thing would be called off. Richard and Carolyn drove over to New Chinatown. Rather than invite the couple in, Fong See stood with them in the courtyard outside his store. To Carolyn, he seemed older than God. He wore long Chinese robes, and she watched, bewildered, as he gibbered and twitched and—to her mind—gave an imitation of a crazy old Chinaman. He pinched her behind. He pinched her arm. He said, “Good stock.” Then he turned to Richard and asked, “You got five dollars?”

“I’m thinking of getting married, and I wanted to ask you if it’s okay,” Richard said.

Fong See didn’t say no.

The next day, Carolyn went to see her mother. At no time did the words “I might be pregnant” enter into the discussion. Again, the announcement of her upcoming marriage was done in the same jaunty fashion as going to a jazz club or out for a pizza. Carolyn remained upbeat, cheerful, a little ditsy.

“Richard’s a nice man,” she explained. “He wants to grow a beard, but it’s not a pose, because his father has one. He has black hair and green eyes, and he skis …”

Eddy (with his December 7th beard), Stella, Sissee, and Gilbert at the Earl Carroll Theatre Restaurant in Hollywood, late 1940s.

Ray See as a successful businessman, late 1940s.

Chuen, Yun, an unidentified friend, and Richard, with their fishing gear, early 1950s.

Ray with friends at New Chinatown.

Stella and Eddy in late 1940s or early 1950s.

See-Mar showroom

Fong See outside the Los Angeles Street store just before it was torn down, c. 1949.

Exterior of F. Suie One Company on Ord Street.

Interior of F. Suie One Company, showing old China City kiosks.

Richard as a cute high school student.

The wedding of Richard See and Carolyn Laws, 1954.

Fong See as a very old man.

Gilbert Leong, successful architect, with Miss Chinatown.

Lisa in the F. Suie One Company, 1963.

Ming and Bennie (seated) in the “shop” at the F. Suie One Company on Ord Street in 1960s.

Eddy and Peanut at work.

Stella and Sissee, November 5 , 1988. On this night the F. Suie One Company received Centennial Honors from the Chinese Historical Society of Southern California for “a century of excellence in pioneering achievements as a member of the Chinese American community in Southern California.”

Ngon Hung celebrates her eightieth birthday in 1987, with Sumoy and Frank Quon.

Sissee’s seventy-fifth birthday, 1984. Top row: Si (Gilbert’s brother-in-law), Margie (Gilbert’s sister), Gilbert, Nick Nichols, Bernice (Gilbert’s sister-in-law), and Yun Fong. Bottom row: Stella, Ngon Hung, Leslee, Sian (Leslee’s daughter) Elizabeth (Leslee’s cousin), and Sissee.

Leslee Leong with her daughters, Sian and Mara (seated), 1989. (Adam Avila)

Alexander See Kendall and Christopher Copeland Kendall, 1994. (Patricia Williams)

Lisa and relatives have lunch in Foshan (formerly Fatsan), China, 1991.

Lui Ngan Fa, Fong Yun’s concubine, in Foshan, 1991.

Fong See’s house in Dimtao, China, 1991.

The F. Suie One Company in Pasadena, 1995.

“Is he in school?”

“He’s in the army, but he wants to be an anthropologist.”

“And his family?”

“They’re very close,” Carolyn went on. “That’s the way they do things, at least that’s what Richard says. Family is everything to them, and even though they’ve lost a lot of traditions in this country, there’s still a big effort to keep it all going.” Carolyn hated it that she was taking the very words that had so upset her when they had come out of Eddy’s mouth and using them to sell her mother on Richard. But this way of keeping the conversation going also kept her mother from saying anything mean. “Richard says it’s their identity crisis, so that they can subdue the stresses that impinge upon any marginal subculture in this society …”

“What is Richard?”

“What do you mean, ‘What is Richard?’”

“You know what I mean.”

“Didn’t I tell you? He’s a quarter Chinese, didn’t I mention that?” Then, not caring after all, she added the phrase that Richard had learned from Anna May Wong: “Oh, Mother, fifty million Chinamen can’t be Wong.” No laughs, but no objection either.

Visiting George and Wynn turned out to be far more of a trial. George sat Richard down for three hours of homespun Southern wisdom on marriage, family, and the responsibilities of a man and wife.

“Happiness is the absence of aggravation,” George proclaimed. “A clean conscience is a comfortable companion. What’s good for you is bad for you.”

“I’m sure we’ll be happy,” Richard ventured.

“I don’t give a damn what you say, kid. In your youth and loyalty you may feel required to say you love Pee Wee so much you’d trust her drunk, undressed, and in bed with Errol Flynn.”

“Daddy …”

“Pee Wee, forget yourself for the next few months and think instead of Richard, or Richard-and-Carolyn, as a married unit. Put some personal sacrifice in the bank for the long months ahead. I want you to invest in a little insurance for the years to come—insurance of a life free from the fl

ippant crack and the lifted eyebrow.”

As Wynn came in with iced tea for everyone, George went on, “I happen to like Richard and think he’s a good dish for any girl, you included. Now you must think I’m for sure a cornball.”

“Oh, George,” Wynn said.

“All I’m saying is, don’t ever get daunted.”

As they got in the car, Richard sighed, “My God, that man needs to drink.”

Looking at this round of visits, Carolyn saw only that her family was extremely relieved. Everyone was supposed to get married, settle down, have kids. The fact that the Sees were Chinese and that the state’s miscegenation laws had been overturned not quite six years before? No one cared. Kate was lost in anger about her own life, Wynn thought the marriage was cool, and George was relieved of his guilt.

Still, Eddy fought the idea of his son marrying Carolyn. Eddy took George out for tea cakes, and tried the same arguments that he’d used on Carolyn and Richard: they were both too young; they weren’t up to the responsibility of a family. Finally, desperately, he said, “Carolyn doesn’t know how to make bao. Richard should really marry a Chinese girl.”

“You didn’t,” George pointed out.

“Yes, but Stella had our whole family to help her. Your daughter won’t have a Chinese motherin-law.” Then Eddy laughed as though it was an intolerably funny joke. Except that it wasn’t a joke at all. This was the crux of it. Although his father had married a white girl and he himself had married a white girl, it was heartbreaking to think that his son would marry one. Just like his friends and neighbors, Eddy, the most “Chinese” of all the brothers, had hoped for a Chinese daughter-in-law—American-born would have been fine.

For the next week, Richard and Carolyn were caught up in a round of activities. They went to La Golondrina on Olvera Street for dinner. They saw One Summer of Happiness again. Carolyn threw up at work—another sign that she might be pregnant—then went to the movies with a friend. The day after that, Carolyn and Richard got their blood tests and went to another movie. The following day they got their license, and Eddy made Carolyn a ring out of twenty-four-carat gold. That night they had dinner with Kate. The next day Carolyn bought a wedding dress—a pale blue linen dress with a little matching hat—and an outfit to wear to the wedding banquet—a tangerine silk blouse and a navy blue skirt. These purchases left her stone broke. That evening, the night before the wedding, they had dinner with Stella and Eddy in Chinatown.

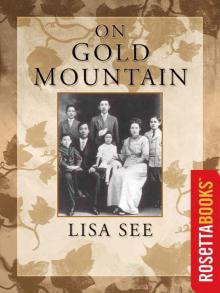

On Gold Mountain: The One-Hundred-Year Odyssey of My Chinese-American Family

On Gold Mountain: The One-Hundred-Year Odyssey of My Chinese-American Family Snow Flower and the Secret Fan

Snow Flower and the Secret Fan Peony in Love

Peony in Love Flower Net

Flower Net Dragon Bones

Dragon Bones Shanghai Girls

Shanghai Girls Dreams of Joy

Dreams of Joy The Island of Sea Women

The Island of Sea Women The Tea Girl of Hummingbird Lane

The Tea Girl of Hummingbird Lane China Dolls

China Dolls The Interior

The Interior On Gold Mountain

On Gold Mountain